Far too often, health systems rely on fragmented, episodic data that provide only temporary glimpses into complex realities. While valuable for immediate diagnostics, one-off surveys and snapshot assessments are insufficient for tracking progress, diagnosing systemic weaknesses, or implementing long-term reforms. This limitation is especially critical in resource-constrained environments where efficient and equitable service delivery is vital.

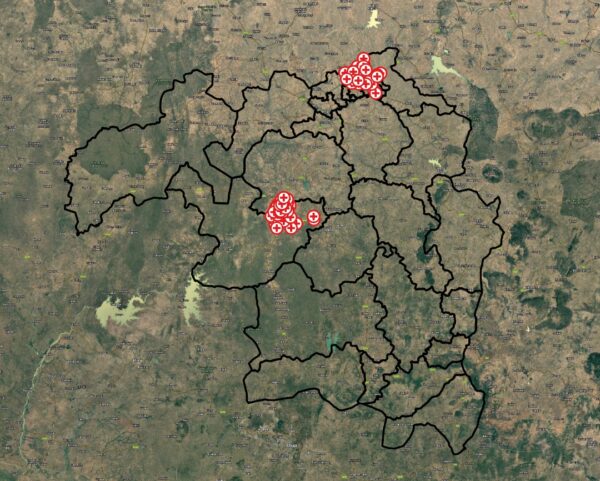

This is precisely the challenge that the NFTI Longitudinal Study is tackling in Kaduna State, where the foundation is consistently collecting and analyzing health system data across Kaduna North, Kaduna South, Chikun, and Makarfi LGAs over time. The study aims to understand not just what is happening, but why, how, and with what consequences. It is an approach to public health monitoring, one that introduces nuance, continuity, and a focus on outcomes rather than optics.

However, to fully realize the potential of this longitudinal model, the integration of Geographic Information Systems (GIS) has become indispensable. Geospatial technology provides the essential spatial layer that transforms numbers into narratives and locations into living stories. Through accurate mapping and facility polygonization, GIS ensures that data are both credible and contextually anchored, enabling decision makers to act with precision.

Health is inherently dynamic. Medicine stock levels fluctuate. Staffing varies by season, by LGA, and even by daily workloads. Service quality can shift subtly over months or overnight. Traditional, one-time surveys may record these events, but they rarely explain them. A snapshot might indicate a well-stocked facility, but it cannot reveal whether drug shortages are recurring. Similarly, a single data point may show staff presence, but without temporal tracking, it fails to highlight absenteeism patterns tied to burnout or systemic inefficiencies.

The NFTI Longitudinal Study is purpose-built to address this data deficit as it regularly collects important information, like how many healthcare workers are available, the amount of essential drugs and vaccines in stock, how well facilities are working, and how reliable the supply chain is, over time. This reveals patterns, spots systemic risks, and gives policymakers useful insights, enabling decision-makers to address root causes instead of reacting to symptoms.

Moreover, the longitudinal approach adds a human element to healthcare data. It tells the story of communities—how they change, grow, and respond to interventions. It offers insights into what works, what doesn’t, and how interventions can be better tailored to meet real needs. Over time, the result is a living dataset that describes the system and learns from it.

Yet, even the best data can fall short if its spatial dimensions are poorly understood. In Kaduna State, as in many parts of the developing world, public health facilities have long operated with vague or outdated geographical identifiers. Without clear knowledge of where these facilities are, how far they extend, or whom they serve, it becomes nearly impossible to plan effectively.

Accurate facility mapping—particularly through polygonization—fills this crucial gap. By converting facility point locations into precise geographical polygons, stakeholders can determine actual service coverage areas, identify underserved communities, detect overlapping jurisdictions, and plan future investments with clarity.

Health Facilities Captured in Longitudinal Study Across 4 LGAs

For example, understanding the physical footprint of a facility in relation to population density allows for better alignment between supply and demand. It enables planners to assess whether the facility’s size and resources are adequate for the community it serves. It also supports emergency preparedness, logistical planning, and equitable resource distribution. Without this level of granularity, health interventions risk being misaligned, misdirected, or misinformed.

The integration of GIS into the longitudinal study transforms what would be a rich but abstract dataset into a fully contextualized decision-making tool. It offers spatial clarity for temporal insights. For instance, a detected decline in drug availability can now be mapped to specific facility polygons, revealing whether the issue is location-specific, systemic, or tied to environmental or logistical factors.

Moreover, GIS enables data layering: facility extents can be overlaid with data on population density, disease outbreaks, transportation routes, and more. This spatial intelligence helps stakeholders target interventions more effectively, whether it’s deploying mobile clinics to hard-to-reach communities or rerouting supply chains for efficiency.

In this context, GIS not only enhances the credibility of data but also secures it, introduces scale and precision, and uncovers patterns that are not readily visible.

Crucially, this initiative is not unfolding in isolation. NFTI is working closely with government agencies, healthcare workers, the Gates Foundation, its data champion network, and community stakeholders. This participatory approach ensures that data collection and mapping reflect actual realities and that the insights generated are both technically sound and socially grounded.

In the short term, GIS-enhanced longitudinal data allows health authorities to respond swiftly to gaps, be it staff shortages, drug stockouts, or infrastructure issues. In the medium term, it supports strategic resource planning and more equitable service delivery. And in the long term, it builds a resilient, responsive, and evidence-based healthcare system in Kaduna State.

The marriage of longitudinal data and geospatial mapping is a technical evolution in public health monitoring. In Kaduna State, it is enabling a shift from reactive policies to proactive planning, from generalized assumptions to pinpoint accuracy. Investing in accurate data mapping and GIS-powered analysis is enhancing data credibility and giving life to a new era of healthcare accountability and equity.

Written by: Simnom Emanuel, Communications Specialist, NFTI.

Contributor: Ayobami Iyanda, Data Analyst, NFTI.